Mariano Herrera

La sombra de un rio

96 pages

24x30cm

Hardcover

Edition of 600 copies

Kominek Books 2024

-

“Words and pictures are two different animals” (William Eggleston)

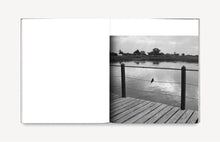

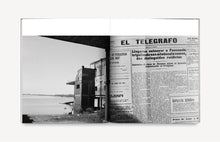

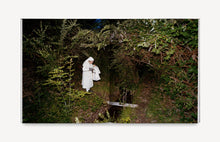

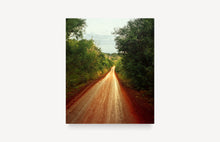

In 1933 Eric Pixton left Buenos Aires aboard the Lybo, a kayak made of canvas with his rows, a couple of sails and 150 kilograms of equipment. His goal was sailing the Uruguay river upstream about 1200 kilometers, through the boundaries of Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil to the Iguazu Falls. Pixton’s trip became a book published in 1936 by Argentinian publisher Peuser and then fell into oblivion. Almost a century later, Mariano Herrera (Buenos Aires, 1970) followed Pixton’s river trails with his camera. Instead of just reenacting a forgotten expedition, The shadow of a river reflects on time and memory while portraying life on the shores that end in the Paraná delta, South America 's second largest river.

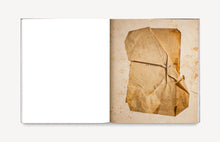

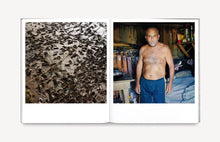

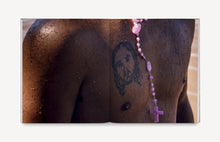

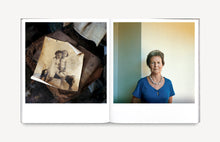

Soon Pixton’s traces become the building blocks of Herrera’s own visual narrative. Old memorabilia about the original adventure is intertwined with recent portraits and written stories about the delta inhabitants.

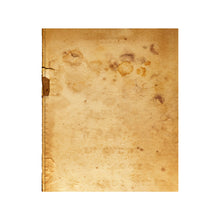

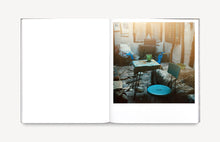

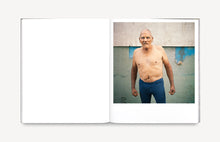

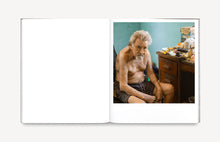

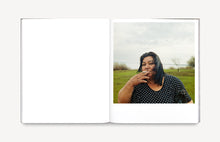

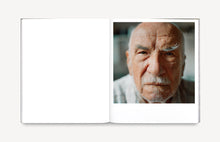

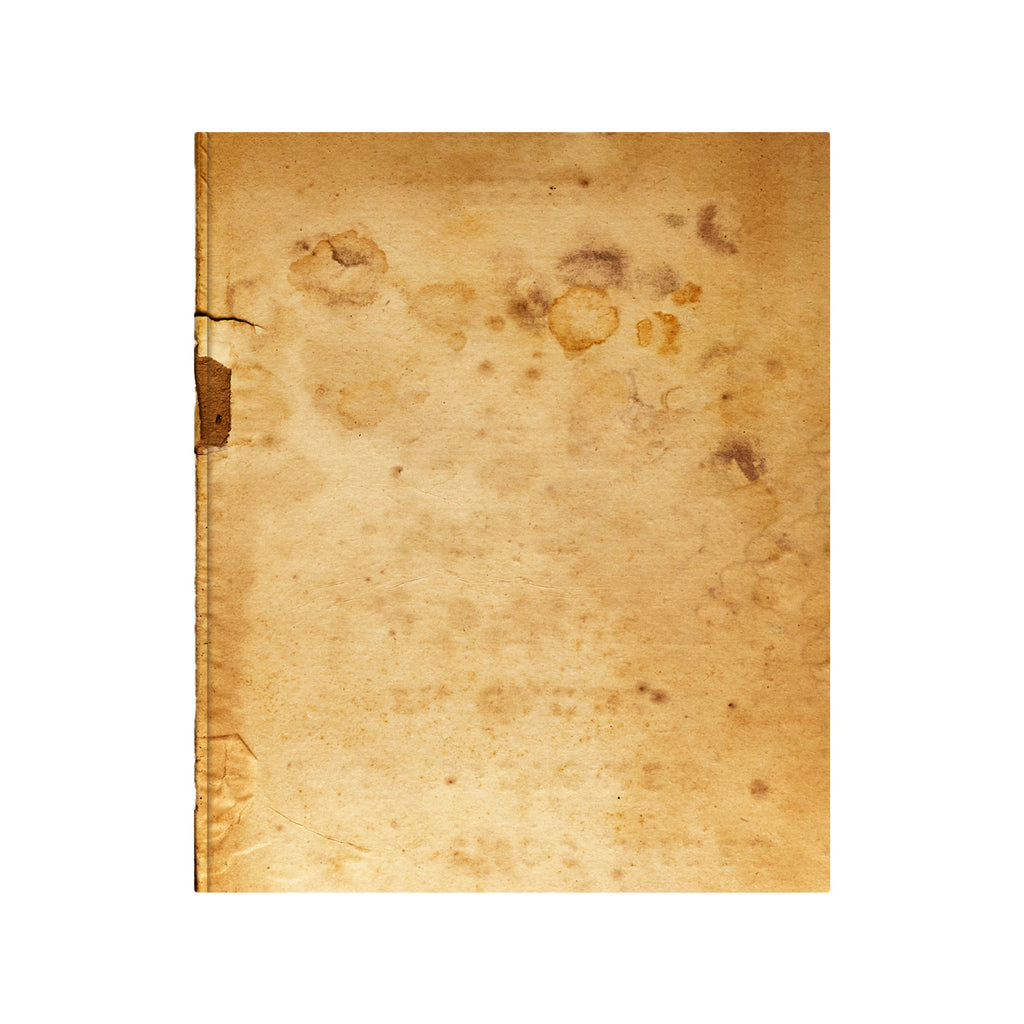

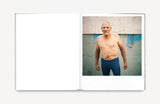

A mix of past and present but also fact and fiction, where places and people are inevitably eroded by the sediments of the Uruguay brownish waters. The passing of time is ever present in Pixton’s worn pictures, yellowed pages and crumpled handwritten notes. Same happens with the half-abandoned settings and battered old faces Herrera comes across. Riverside people who sit on a porch, have a drink, stand on a corner or just lie in bed. Staring at the camera against damp walls, rusty teapots or wooden rooms decorated with knives. A similar mood overflows Pixton’s past evocations and Herrera’s renewed images, as if the river shaped all life forms around it now and then. Wet or muddy bodies seem to be molded by its endless flow. Humans and creatures swim and rest by its waters, until the starry night falls upon the riverside by the forest. Just like the dusty documents where Pixton tried to capture his elusive memories, the decayed homes and factory ruins captured by Herrera look like useless attempts to build some lasting development against nature’s inexorable ways.

The book alternates color with black and white, newspaper clips, old archives and typewritten paper sheets that acquire the same tonality as the river. Herrera’s taste for real people in their everyday environment strays from any exuberant or idealized views of the region. The transition between his pictures and Pixton’s becomes intentionally blurry, until both memories seem to be carried away by the waters. This subtle mixture acts as a visual reminder that all things must and will pass, unlike nostalgic revamps of the past like retrofuturism and steampunk. Herrera’s personal interpretation of the wild Uruguay riverside looks back and inwards, like true literature and travel should.